Time has become such an important aspect of modern civilization that people have difficulty conceptualizing the possibility of ancient cultures viewing time any differently than we do today (Whitrow 3). In fact, as Whitrow observed, “[f]or many people the way in which we measure time by the clock and the calendar is absolute” (3). Human beings in the modern world believe tend to believe time is a historical given, shared universally across all people and all ages (Whitrow 3). Nonetheless, if one takes a historical perspective and looks back across the timeline of human civilization, one begins to see how notions of time emerged initially and how they have evolved over the course of the centuries; one even notices how time was thought of and treated differently by disparate societies and cultures.

Although the historical record indicates that the Egyptians had no “single, unequivocal term for ‘time’ in [their] vocabulary” (Dunand & Zivie-Coche 43), the ancient Egyptians were largely responsible for defining time as Western cultures now know it, devising the notions of hours and days as temporal units, as well as establishing the social norms by which people related to time (Whitrow 24). By examining the history of the concept of time as it was developed by ancient Egyptians, one can, perhaps, come to understand contemporary people’s relationship with time from a more knowledgeable perspective.

Many ancient societies, tied closely to their land, did possess notions of time, even if their ideas were not articulated or formalized in theories. The ancient Egyptians, for instance, were intimately familiar with the cycles of the seasons and the fluctuations in climate and tides; the mighty Nile River cut through their territory and it was the Nile upon which they depended for sustenance and commerce (Whitrow 24). “[E]verything,” wrote Whitrow, “depended on the Nile” (24), and he did mean everything. From making the determination of when to plant and harvest crops to scheduling the appropriate moment for installing a new pharaoh, the ancient Egyptians rendered their most important decisions by looking to such aspects of the environment as when the river rose and when its waters fell (Whitrow 24).

There were patterns to be discerned in these environmental elements, and the ancient Egyptians began to develop a concept of time based on this “succession of recurring phases” (Whitrow 25), which today, of course, our culture refers to as the seasons. The recognition of seasons and the cycle of birth, life, death, and rebirth was the first element of time identified by the Egyptians, the largest unit of time, and one which would form the framework into which the other units of time could be set. The idea most fundamental to ancient Egyptians’ view of time was that it was cyclical, not linear, “made up of periods that renewed themselves….” (Dunand & Zivie-Coche 52). These periods were the “daily rising of the sun…, the annual return of the foundation and beginning of the year, and… the succession of the reigns of the pharaohs” (Dunand & Zivie-Coche 52). Thus, one sees how the observed world and the lived world coincided through the emergent ideas about time advanced by the ancient Egyptians.

Before moving on to explain how the ancient Egyptians identified the other units of time, such as day, night, and hours, it is important to explain what function the view of life as a cycle of seasons played in Egyptian life (Dunand & Zivie Coche 42). As TenHouten explained, “A theory of time and society requires a model not only of time but also of society….” (x), thus it becomes critical to understand how societies shape concepts of time to fit their arbitrary social needs and how, over time, these concepts become integral to maintaining the social order and structure.

For the Egyptians, the units of time they were developing served not only the purposes of farming and the ritualization of certain social celebrations, but also supported the fundamental beliefs of their culture (Meskell 423; Whitrow 25). Whitrow wrote that the ancient Egyptians had “very little sense of history or even past and future,” and that they thought of the world as “static and unchanging” (25). The seasons, then, predictably repeated in a never-ending cycle, affirmed “cosmic balance” and “inspired a sense of security from the menace of change and decay” (Whitrow 25). As Bochi remarked, time was both immutable and pervasive for the ancient Egyptians (51). This fact did not, however, preclude the ancient Egyptians for devising both the concepts and the words to explain time.

The idea of seasonal cycles was not only important for propagating agricultural crops. In fact, Meskell has argued that the ancient Egyptians came to view their individual lives as cyclical as well (423). The narrative ancient Egyptians began to live and tell about themselves played out in a trajectory of “pregnancy, birth, childhood, adolescence, adulthood, old age, and death” (Meskell 423); each generation could gain comfort and security from knowing its life story would unfold in the same cycle as the generation that preceded it. What is still more fascinating, however, is that this belief seemed to be embodied in virtually every aspect of Egyptian culture and daily life.

Meskell pointed out that the symbolism of the life cycle and the degree to which it permeated the ancient Egyptian village can even be substantiated by archaeologists, who have discovered that the placement of the deceased members of the community was “layered in terms of a life cycle,” with “neonates buried at the base of the slope [of the village], followed by children and adolescents mid-slope, and adults…buried at the high point of the hill” (Meskell 423). Clearly, cycles, seasons, and the evolving conceptualization of time were so important to the Egyptians that they were not only shaped by their beliefs and their culture, but came to be so influential as to reshape beliefs and culture, or, at the very least, to reaffirm them.

Despite this apparently rigid and faithful adherence to the emerging notion of time, one may observe that it was interesting that the need to believe in a cyclical theory of time did not translate—at least not immediately—to the notion of a year. Again, because time serves specific and subjective social functions, the Egyptians did not count time in annual units that proceeded chronologically (Whitrow 25). Rather, they marked time according to significant social events, and effectively stopped and started years when it was convenient for them. As Whitrow explained, “The years were… numbered…according to a particular pharaoh’s reign, each mounting the throne in the year 1, and also according to the levy of the taxes” (25). Because taxes were levied every two years, years were effectively rolled back and the clock started anew.

This utterly unique system of numeration of the years has complicated historians’ and archaeologists’ understanding of the chronology of ancient Egyptian culture, but it underscores the observation that time was adapted at the society’s collective and subjective whim to support its social values and norms. These facts seem to support TenHouten’s argument that time can be and is viewed from biological, cognitive, and social dimensions, but beyond these attributes, it also remains highly subjective (x; 5).

Given the preceding facts, it may seem surprising that it was the Egyptians who devised the 365-day calendar which remains in use—and is the dominant model for time measurement—centuries later (TenHouten 222; Whitrow 25). In addition to their lunar calendar, the ancient Egyptians developed a 365 day calendar, which was appropriated by Greek and Middle Age astronomers, Copernicus among them (TenHouten 222). Yet the reason why the calendar was developed appears to have been thoroughly pragmatic. By watching and marking the cycle of the Nile’s rising and receding, the cycle of seasons was identified and farming could become more predictable and, presumably, more successful (Whitrow 25). The 365 day calendar was divided into three seasons: the “time of inundation, sowing time, and harvest time” (Whitrow 25).

Each season had a duration of four months, so the entire year totaled 12 months (Mainzer 4). The ancient Egyptians retained the calendar throughout the entire course of their civilization, cognizant of the calendar’s “convenience as an automatic record of the passage of time in an era….” (Whitrow 26). It was adapted occasionally as new discoveries were made, but the essential structure and philosophy of the calendar remained intact.

The ancient Egyptians’ theories about and relationships with time did not end at the season and year. Starting with these larger units of time, the Egyptians worked their way to smaller and smaller units, reducing time to mere fractions. For instance, although cultures both contemporaneous with and subsequent to that of the ancient Egyptians would adopt “[a] wide variety of conventions…for deciding when the day-unit begins,” ancient Egyptians chose dawn as the arbitrary and symbolic start of the new day (Whitrow 15). Clearly, the Egyptians’ choice was adopted as a standard in the Western world; today, we still recognize dawn as the start of a new day.

With the idea of the day in place, the Egyptians further classified time into arbitrary units that would come to have meaning and influence for centuries to come. As Whitrow explained, the ancient Egyptians were responsible for “[t]he [further] division of the daylight period into twelve parts….” (17). The time between sunrise and sunset was apportioned into ten segments that came to be known as hours; two additional hours, one for dawn and one for twilight, were added, for a total of 12 daytime hours (Whitrow 17). Night was similarly divided into 12 segments; together, day and night became a single cycle of 24 hours, a unit for marking the passage of time (Whitrow 17). As would also be true of later cultures, the ancient Egyptians relied heavily upon the changing positions of the stars to tell what the hour was at any given moment (Mainzer 3).

As their civilization advanced, so too did their concepts of time evolve; however, the Egyptians themselves did not take credit for devising a systematic, non-linear approach to organizing and understanding time (Dunand & Zivie-Coche 65). Instead, the Egyptians credited their gods and goddesses for introducing the idea of cyclical time divided into various units. In fact, in what Dunand and Zivie-Coche described as “a major hymn” to the goddess Neith, Egyptians chanted: “She made the moment,/she created the hours,/she made the years,/she created the months,/and she gave birth to the season of inundation, to winter, [and] to summer” (65). Viewed in this way, time was not malleable in the hands of the Egyptians themselves.

In the same way that time was introduced by the gods and goddesses, so too was it controlled by the deities (Dunand & Zivie-Coche 65). Despite the idea that life was a cycle that ended with death, the ancient Egyptians believed that death was merely a doorway into the next life, “the moment of a passage to another time” (Dunand & Zivie-Coche 65). Again, evidence from the archaeological record supports just such an argument, as ancient Egyptians were buried with the goods it was believed they would need to carry into the next lifetime (Budge 466). Historical time, that is, time on earth, was viewed “only as an application…on the human level” (Dunand & Zivie-Coche 66). Cosmic time, on the other hand, which was managed by the gods and goddesses, was the supreme expression of temporality (Dunand & Zivie-Coche 66).

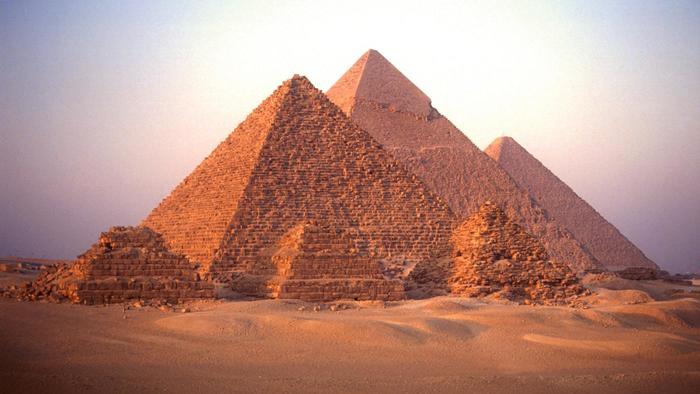

Because the gods and goddesses were responsible for time, and because they alone determined the favor or difficulty that time would impose upon the Egyptian people, the ancient Egyptians’ physical structures and institutions were constructed in such a manner that their presence celebrated and affirmed the centrality of a time-consciousness in their culture (Dunand & Zivie-Coche 90). The physical structures of temples and pyramids were as carefully regimented and attentive to numeric division as time itself was (Dunand & Zivie-Coche 90). Furthermore, what occurred inside the temples through the performance of daily rituals also reaffirmed how time conscious the ancient Egyptians were (Dunand & Zivie-Coche 90). Daily rites and rituals were timed precisely to coincide with the specific environmental phenomena—such as dawn—that marked time for Egyptians. “The life of the temple,” wrote Dunand and Zivie-Coche, “began at dawn” (90), an observance that continues in the Muslim world to the present day.

In ancient Egypt, religious officiants were charged with performing tasks that signaled the literal and spiritual dawn of a new day. The first task was to prepare food made of the offerings laid on the altar by devoted Egyptians: “loaves, cakes, vegetables, fruits, red meat, and fowl….” (Dunant & Zivie-Coche 90). Once the offerings were acknowledged, the priest proceeded to break “the clay seal on the door of the holy of holies [and] chant the morning hymn, ‘Awake, great god, in peace! Awake, you are at peace’” (Dunant & Zivie-Coche 90).

The breaking of the seal was followed by replacing the previous night’s candle and breaking still another seal, this one on the door of a cabinet hiding a deity statue. This act of ensuring that the god had been “[brought] to life after a night of sleep” confirmed that night had ended and a new day had begun (Dunant & Zivie-Coche 90). These were just the first in a series of ritualized actions that were performed to signal the passage of time, the transition from one day to the next, and the meaning it had for gods and mortals alike.

The ancient Egyptians are credited for introducing an astonishing number of ideas and practices that have remained central to human civilization. In his 1847 catalog of Egyptian culture, The Manners and Customs of the Ancient Egyptians, Wilkinson credited Egyptians with inventing everything from agricultural irrigation, measurement systems, and codified writing to more abstract and idealistic ideas and institutions, including social castes and the legal and justice systems.

Perhaps one of the most significant and lasting among the ancient Egyptians’ numerous contributions to human civilization, however, is the conceptualization of time which they developed and handed down to subsequent societies and generations. Although modern human beings are less inclined to see time as an attribute of life prescribed and overseen by the gods, and are more likely to view time as a universal feature of life that has existed, both immutable and unchanged, across all time and space, a review of the literature on the subject of the development of time as a concept indicates that the ancient Egyptians were largely responsible for introducing the concepts of time that we now hold so central to our own culture.

Egyptians were, in short, clock-watchers. Time was deeply important to the Egyptians, ensuring not only their physical survival, but providing the psychological, spiritual, and social rationale to substantiate their religious and cosmological beliefs. This ancient civilization, in many ways so different from our own, developed a cosmology of time that was derived from their religious beliefs and which served to reaffirm and honor those beliefs.

While the ancient Egyptians credited their gods and goddesses with giving them the gift of knowledge and understanding about time, it was they who were responsible for identifying and defining the units of time according to which most of the world—its people and its institutions—operated today in the 21st century. Centuries after the decline of the ancient Egyptian culture and civilization, modern human beings continue to find value and meaning in the cyclical notion of time that was first presented by the Egyptians. Although our theories of time have become far more complex and sophisticated, and our understanding of just how profoundly time both influences and is influenced by a society’s subjective biological, cognitive, and psychosocial needs has deepened (TenHouten 22), time remains as important a human construct today as it was for the Egyptians millennia in the past.

Works Cited

Bochi, Patricia A. “Time in the Art of Ancient Egypt: From Ideological Concept to Visual Construct.” KronoScope 3.1 (2003): 51-82.

Budge, E.A. Mummy: A Handbook of Egyptian Funerary Archaeology. New York: Dover, 1989.

Dunand, Francoise, and Christiane Zivie-Coche. Gods and Men in Egypt: 3000 BCE to 395 CE. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2004.

Mainzer, Klaus. The Little Book of Time. Munich, Germany: C.H. Beck Verlag, 1999.

Meskell, Lynn. “Cycles of Life and Death: Narrative Homology and Archaeological Realities.” World Archaeology 31.3 (2000): 423-441.

TenHouten, Warren D. Time and Society. Albany, NY: SUNY Press, 2005.

Whitrow, G.J. Time in History: Views of Time from Prehistory to the Present Day. New York: Oxford University Press, 2004.

Wilkinson, John Gardner. The Manners and Customs of the Ancient Egyptians. London: Oxford University, 1847.

- Abuse & The Abuser

- Achievement

- Activity, Fitness & Sport

- Aging & Maturity

- Altruism & Kindness

- Atrocities, Racism & Inequality

- Challenges & Pitfalls

- Choices & Decisions

- Communication Skills

- Crime & Punishment

- Dangerous Situations

- Dealing with Addictions

- Debatable Issues & Moral Questions

- Determination & Achievement

- Diet & Nutrition

- Employment & Career

- Ethical dilemmas

- Experience & Adventure

- Faith, Something to Believe in

- Fears & Phobias

- Friends & Acquaintances

- Habits. Good & Bad

- Honour & Respect

- Human Nature

- Image & Uniqueness

- Immediate Family Relations

- Influence & Negotiation

- Interdependence & Independence

- Life's Big Questions

- Love, Dating & Marriage

- Manners & Etiquette

- Money & Finances

- Moods & Emotions

- Other Beneficial Approaches

- Other Relationships

- Overall health

- Passions & Strengths

- Peace & Forgiveness

- Personal Change

- Personal Development

- Politics & Governance

- Positive & Negative Attitudes

- Rights & Freedom

- Self Harm & Self Sabotage

- Sexual Preferences

- Sexual Relations

- Sins

- Thanks & Gratitude

- The Legacy We Leave

- The Search for Happiness

- Time. Past, present & Future

- Today's World, Projecting Tomorrow

- Truth & Character

- Unattractive Qualities

- Wisdom & Knowledge

Comments