Post-publication activity

Curator: David Myers

To psychological researchers, happiness is life experience marked by a preponderance of positive emotion. Feelings of happiness and thoughts of satisfaction with life [1] are two prime components of subjective well-being (SWB).

The scientific pursuit of happiness and positive emotion is also the first pillar of the new positive psychology first proposed in Martin E. P. Seligman’s 1998 American Psychological Association presidential address. Positive psychologists also study positive character strengths and virtues and positive social institutions.

Contents |

Assessing Happiness

Psychologists assess people’s happiness with varied measures. The simplest is a single item that has been posed to hundreds of thousands of representatively sampled people in many countries: “Taken all together, how would you say things are these days─would you say you are very happy, pretty happy, or not too happy?”

Other investigators employ multi-item happiness measures. Some tap into the “cognitive” component of happiness (i.e., judgments of high life satisfaction) and others assess the “affective” component (i.e., the experience of frequent positive emotions and relatively infrequent negative emotions). For example, the popular Satisfaction With Life Scale asks respondents five questions about their feelings regarding their lives (e.g., “In most ways my life is close to my ideal.”) Other measures assess the affective component of happiness in different ways. The Affect Balance Scale invites people to report how frequently they have experienced various positive and negative emotions over the last 30 days. The Experience Sampling Method uses a pager to occasionally interrupt people’s waking experience and to sample their moods, and the Day Reconstruction Method requires respondents to review their previous day hour by hour and to recall exactly what they were doing and how they were feeling during each hour.

Multi-item global measures of happiness are also frequently used by researchers. The Subjective Happiness Scale asks people to rate the extent to which they believe themselves to be happy or unhappy individuals (e.g., “In general, I consider myself…,” with the options being somewhere between “not a very happy person” and “a very happy person”).

How Happy are People?

Contrary to many reports of abundant misery (“Our pains greatly exceed our pleasures,” said Rousseau), most people report being “fairly” or “very” happy and relatively few (some 1 in 10 in many countries, including the USA) report being “not too happy.” Pioneering happiness researcher Ed Diener aggregated SWB data from 916 surveys of 1.1 million people in 45 nations that represent most of the human population. When responses were converted to a 0 to 10 scale (with 5 being neutral), the average SWB score was near 7.

Likewise, when people’s moods have been sampled using pagers or in national surveys, most people report being in good rather than bad moods.

These generally positive self-reports come from people of all ages and both sexes worldwide, with a few exceptions: people hospitalized for alcoholism, newly incarcerated inmates, new therapy clients, South African blacks during the apartheid era, homeless people, sex workers, and students living under conditions of political suppression.

When surveyed, there is some tendency for people to overreport good things (such as voting) and underreport bad things (such as smoking). Yet people’s SWB reports have reasonable reliability across time and correlate with other positive indicators of well-being, including friends’ and family members’ assessments. Positive self-reports also predict sociability, energy, and helpfulness, and a lower risk for abuse, hostility, and illness.

Happiness does, however, vary somewhat by country. Recent (1999 to 2001) World Values Survey data collected by Ronald Inglehart from 82 countries indicate highest SWB (happiness and life satisfaction) in Puerto Rico, Mexico, Denmark, Ireland, Iceland, and Switzerland, and the lowest in Moldova, Russia, Armenia, Ukraine, Zimbabwe, and Indonesia.

Who is Happy?

Despite presumptions of happy and unhappy life stages or populations, there are mostly happy and a few unhappy people in every demographic group. Happiness is similarly common among people of differing

- age: Emotionality subsides with maturity and happiness predictors change with age (as satisfaction with health, for example, becomes more important). Yet World Values Surveys indicate comparable SWB reports across the lifespan. For example, self-reported happiness does not nosedive during men’s supposed early 40s “midlife crisis” years or parents’ supposed “empty nest syndrome” years.

- gender: There are gender gaps in misery: When troubled, men more often become alcoholic, women more often ruminate and get depressed or anxious. Yet in many surveys worldwide, women and men have been similarly likely to declare themselves “very happy” and “satisfied” with life.

- race: African-Americans are only slightly less likely than European-Americans to report feeling very happy. Moreover, note social psychologists Jennifer Crocker and Brenda Major, “A host of studies conclude that blacks have levels of self-esteem equal to or higher than that of whites.” People in disadvantaged groups maintain self-esteem by valuing the things at which they excel, by making comparisons within their own groups, and by attributing problems to external sources such as prejudice.

Other indicators do offer clues to happiness.

- The traits of happy people: Extraversion, self-esteem, optimism, and a sense of personal control are among the marks of happy lives. Twin and adoption studies reveal that some of these traits, such as extraversion, are genetically influenced, as is happiness itself. Like cholesterol level, happiness is genetically influenced, yet also somewhat amenable to volitional control.

- The work and leisure of happy people: Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi reports increased quality of life when work and leisure engage one’s skills. Between the anxiety of being overwhelmed and the boredom of being underwhelmed lies the unself-conscious, absorbed state of flow.

- The relationships of happy people: Humans are social animals, with an evident need to belong. For most people, solitary confinement is misery. Having close friends, and being with them, is pleasure. In National Opinion Research Center surveys of more than 42,000 Americans since 1972, 40 percent of married adults have declared themselves very happy, as have 23 percent of never married adults. The marital happiness gap also occurs in other countries and is similar for men and women. The causal arrows between marriage and happiness appear to point both ways: an intimate marriage, like other close friendships, offers social support; but happy people also appear more likely to attract and retain partners.

- The faith of happy people: The same National Opinion Research Center surveys reveal that 23 percent of those never attending religious services report being very happy, as do 47 percent of those attending more than weekly. In explaining the oft-reported greater happiness and ability to cope with loss among people active in faith communities, psychologists have assumed that faith networks may offer social support, meaning, and assistance in managing the “terror” of one’s inevitable death.

Wealth and Well-Being

In the early 21st century, economists and environmental sustainability advocates came to share psychologists’ interest in the extent to which money and consumption can buy happiness. Three in four entering American college and university students (in annual UCLA surveys) say that it is “very important or essential” to “be very well off financially,” and 73 percent of Americans in 2006 answered “yes” when Gallup asked “Would you be happier if you made more money?”

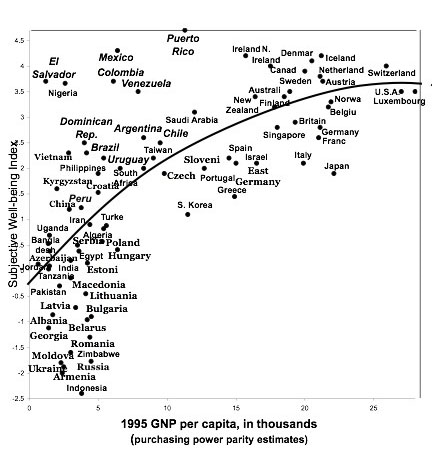

Figure 1: National wealth and well-being. Source: Inglehart, 2006.

In their scientific pursuit of happiness, psychologists and sociologists have asked three questions:

- Are people happier if they live in rich countries? As Figure 1 illustrates, there is some tendency for prosperous nations to have happier and more satisfied people (though these also tend to be countries with high literacy, civil rights, and stable democracies). But the correlation between national wealth and well-being tapers off above a certain level.

- Within any country, are rich people happier? Although many researchers have found the correlation between personal income and happiness “surprisingly weak” (as Ronald Inglehart report in 1990), recent surveys indicate that across individuals as across nations, the relationship is curvilinear: the association between income and happiness tapers off once people have sufficient income to afford life’s necessities and a measure of control over their lives.

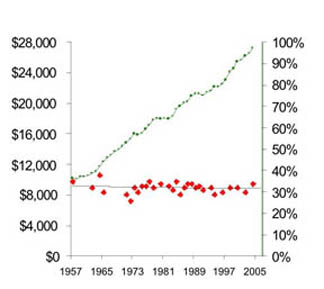

- Does the happiness of a people rise over time with rising affluence? As Figure 2 (which depicts inflation-adjusted disposable income) indicates, the answer is plainly no. Americans love what their grandparents of a half century ago seldom knew: air conditioning, the Internet, MP3 players, and bigger houses. Yet they are no happier. The same is true in other countries, economist Richard Easterlin has reported. Economic growth in affluent countries has not demonstrably improved human morale. Ditto China, where Gallup surveys since 1994 reveal huge increases in households with color TV and telephones, but somewhat diminished life satisfaction. Such results have led Ed Diener and Martin Seligman to collaborate with the Census Bureau in devising new “national indicators of subjective well-being.”

Figure 2: Economic growth and happiness.

American’s average buying power has almost tripled since the 1950s, while reported happiness has remained almost unchanged. (Happiness data from National Opinion Research Center General Social Survey; income data from Historical Statistics of the United States and Economic Indicators.)

Psychologists have sought to explain why objective life circumstances — especially positive experiences — have such modest long-term influence on happiness. One explanation is our human capacity for adaptation. Sooner than we might expect, people will adapt to improvements in circumstances and recalibrate their emotions around a new “adaptation level.” Thus, finds Daniel Gilbert in his studies, summarized in Stumbling on Happiness, emotions have a shorter half-life than most people suppose. Nevertheless, some psychologists, such as Sonja Lyubomirsky and her colleagues, draw from happiness research in designing interventions that aim to increase happiness.

Happiness reflects not only our adaptations to recent experiences but also our social comparisons. As people climb the ladder of success, they tend to compare upward. And with increasing income inequality, as in contemporary China, there will likely be more available examples of better off people with whom to compare. In experiments, people engaged in comparing downward─by comparing themselves with those impoverished or disfigured─express greater satisfaction with their own lives.

References

Daniel Gilbert, Stumbling on Happiness, Knopf, 2006

Jonathan Haidt, The Happiness Hypothesis, Basic Books, 2006

David G. Myers, The Pursuit of Happiness, Harper Paperbacks, 1993.

Martin E. P. Seligman, Authentic Happiness, Free Press, 2002.

Ed Diener and Robert Biswas-Diener, Rethinking happiness: The science of psychological wealth, Malden, MA: Blackwell/Wiley, 2009.

Sonja Lyubomirsky, The How of Happiness,Penguin Press, 2008.

Internal references

- Marc-Oliver Gewaltig and Markus Diesmann (2007) NEST (NEural Simulation Tool). Scholarpedia, 2(4):1430.

- Philip Holmes and Eric T. Shea-Brown (2006) Stability. Scholarpedia, 1(10):1838.

External Links

The Positive Psychology website

The World Database of Happiness

The Journal of Happiness Studies

Research-based suggestions for a happier life

Values in Action “founded to advance the science of positive psychology”

Comments