In July this year, three Colombians were hailed as having the first legal union between three men in the world (Taylor-Coleman, 2017). The three men signed a special legal contract which formalised their union, but it is not a full marriage certificate as it is illegal to marry more than one person in Colombia. Yet, some people are now speculating that the growing number of cases like these could put the question of multiple-person marriages on the agenda.

Multiple-person marriages are illegal in most liberal democracies. This means that in these societies there are people who wish to be polygamous who are unable to legally enter the form of marriage they desire, get the legal benefits of marriage, or associate in marriage with the group of people they would like to. Yet, liberals typically believe that the state should not interfere in a person’s choice of social arrangements unless there were decisive reasons to do so.

The question then arises: should liberal democracies allow multiple-person marriages? Should polygamy be legalised? To justify the illegality of polygamous marriage in modern liberal democracies, it would have to be shown that it would cause significant harm to permit it.

Polygamy as currently practised

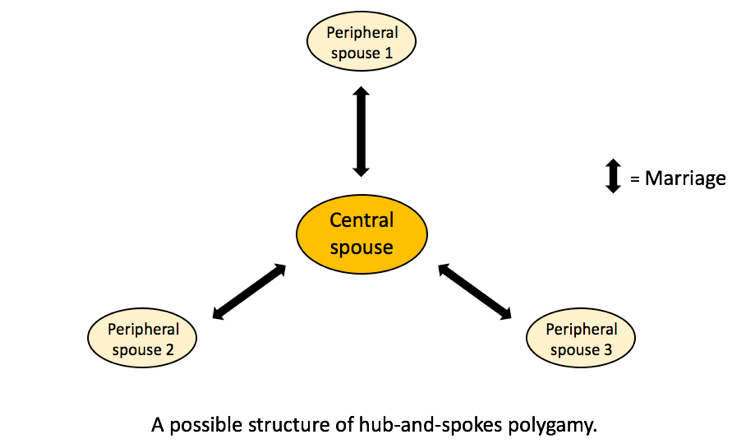

When most people think of polygamy they do not think of the case of the three Colombian men. Instead, they picture what is known as polygyny, a form of hub-and-spokes polygamy. Hub-and-spokes polygamy refers to multiple-person marriages where there is one central individual (the central spouse) who is married to each other person (the peripheral spouses). Polygyny, which accounts for the majority of unofficial/unregistered polygamous marriages in current liberal democracies by far, refers to instances of hub-and-spokes polygamy where multiple women share a husband. It tends to occur amongst a small number of Muslim and Mormon fundamentalist communities.

In principle, there is nothing definitively problematic with the structure of hub-and-spokes polygamous marriages. There are cases in which all of the spouses in such a marriage are unharmed and have willingly entered the marriage due to a genuine preference for polygamy (see Elizabeth Joseph). Nevertheless, there is reason for concern that few real-world cases of polygyny meet these criteria in practice.

Firstly, empirical evidence reveals a troubling correlation between polygyny as it is currently practised and harm to women, a link which judges in many countries have used to uphold bans on polygamy. For example, compared to monogamous women, these women in polygynous marriages are much more likely to experience abuse, depression and poverty (Bala, 2011). Women are often unable to exercise any control over the addition of new wives by their husbands, contributing to feelings of powerlessness and emotional abuse (Hassouneh-Phillips, 2001, 744).

Secondly, there is a reason for concern about whether polygynous wives are meaningfully consenting to their marriages, due to the presence of high levels of social and economic pressure. In North American fundamentalist Mormon communities, there tends to be considerable social pressure for young girls to marry older husbands who will have multiple wives (Macedo, 2015, 170). If they attempt to leave a marriage, they risk losing their social and economic stability, as they are likely to be shunned by their community. Similarly, in certain Muslim communities in the UK, anecdotal evidence suggests that women agree to enter polygynous marriages largely due to the security these provide – although their first preference is for monogamy (“The Men with Many Wives,” 2014).

What about the Colombian men? Polyamory and ‘Webbed Marriage’

Given the problems associated with polygyny, the justification for liberal democracies banning hub-and-spokes polygamy seems reasonable. In particular, the key problems with such marriages that I would highlight are:

- Concern about the harm correlated with polygyny as currently practised

- Uncertainty that the person consented to the marriage due to their own preference for polygamy

- Uncertainty that the person consents freely to the decision to become polygamous, and not under duress stemming from social or economic pressure

But what does this analysis suggest should be done in the case of the Colombian men? It is clear that their legal relationship does not fit into the same category as fundamentalist polygynous marriages; from everything we can glean about their relationship, it does not seem to suffer from any of the problems mentioned above. This primarily stems from the fact that their relationship is not hub-and-spokes polygamy, but is instead a polyamorous relationship.

Polyamorous relationships normally lack a central-spouse-like figure who controls the relationship arrangement, but rather work on the basis of every member of the relationship having an equal say in decision-making. This difference significantly reduces concerns about partners not truly consenting to the arrangement. There is also, so far, no evidence to suggest that polyamory correlates with any empirical harms. General trends in research indicate that polyamorists have similar psychological well-being and relationship quality as monogamists (Rubel and Bogaert, 2015, 961).

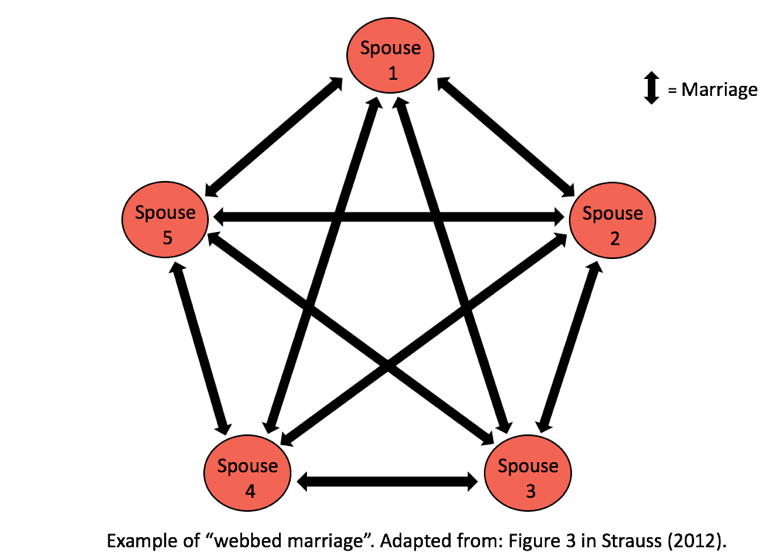

I believe that there is no justified reason for states to prevent polyamorists like the Colombian men from marrying. Polygamous marriages need not be objectionable if the three problems are addressed, and it seems the structure of polyamorous relationships provides us with a blueprint for formulating a form of polygamous marriage which I will call ‘webbed marriage’.

Webbed marriage would allow those who want to have multi-person marriages to do so without cause for concern. In a webbed marriage, every person involved in a relationship has to be legally married to every other member of the relationship. Each person would sign the terms of a collective marriage contract, thereby creating a marital web: a legally binding contractual relationship between them and every other person in the relationship. After this initial contract is created, the legal consent of all spouses would be required before any further people are allowed to join the marital web. If at any point a spouse wanted to divorce from the web, the terms of the original contract would be changed; therefore, the other spouses would have to legally consent once again if they wanted to continue being part of the web. These stipulations mean that in a webbed marriage, each person would be able to veto any proposed change in the structure of the marital web, except for being unable to prevent other members from leaving the marriage.

Conclusion

At the moment, there may be good reasons to keep hub-and-spokes polygamy illegal. However, multiple-person marriages, in general, should not be prevented. The major benefit of this would be that it would finally allow polyamorists to get married. A recent survey of 4000 polyamorous people showed that nearly two-thirds of them would be open to marrying multiple people if it were legal (“What Do Polys Want?” 2012). This would be a significant new option for many of them. Therefore, webbed marriage, if properly fleshed out by local policymakers for their own contexts, could provide an unproblematic form of marriage that is ideal for polygamists, and deserves serious consideration for legalisation in current liberal democracies.

Comments