Almond watched, guided, cajoled to get to this day

'I give (John Almond) a very high grade. To be over the largest public works project in the city, to have it come in the way it has, every aspect has been a success. "

Austin Mayor Kirk Watson

John Almond has a recurring nightmare.

He's back at Oklahoma State University in the late 1960s. He's heading to class to take a final exam. He knows the material cold, and he's ready for it. But as he's walking toward the classroom, he notices his classmates streaming by only they're headed in the wrong direction. “Hey man, where've you been?" they ask. Then it hits him. He missed the test. Filled with panic, he awakens to a sense of slowly dawning relief, freed from the anxiety dream.

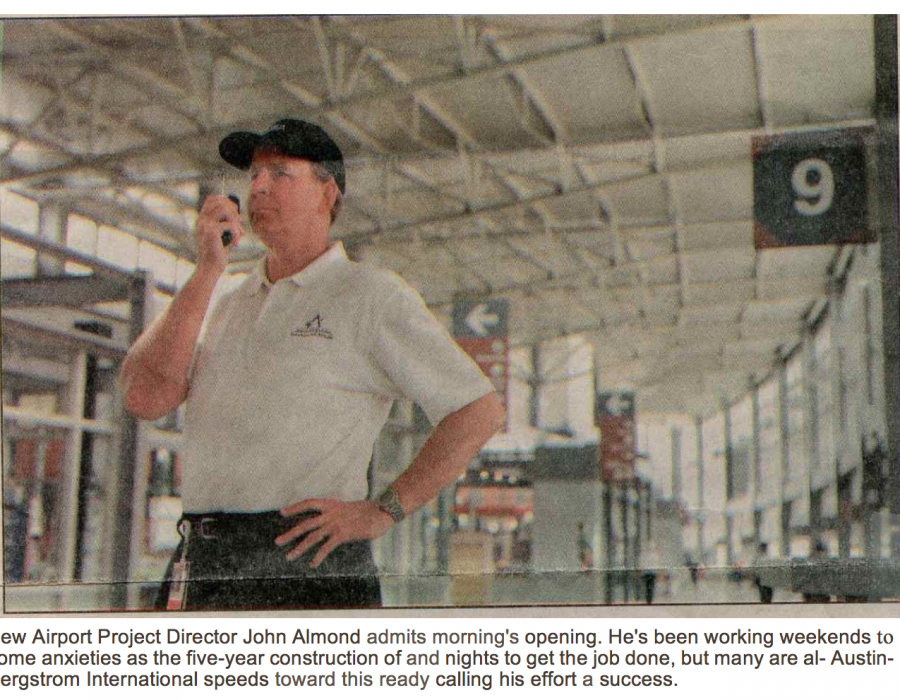

By all appearances, Almond is not an anxious man. As the person at the helm of the largest public works projects in Austin's history, he can't afford to be. Yet he admits to some anxieties in the waning days of the five-year construction of Austin Bergstrom International Airport. And it's no wonder. The final exam for the new $690 million airport won't be over until the planes are in the air today and passengers are flowing in and out.

But some say Almond, 52, has already passed the test. "I give him a very high grade," said Mayor Kirk Watson. "To be over the largest public works project in the city, to have it come in the way it has, every aspect has been a success."

Almond, whose title is new airport project director, is described by those who work with him as a sedate manager in the face of all the day-to-day storms that brew on a project this large. Like the terminal whose construction he oversees, he's more about function than flash. He's quietly decisive and generous with a compliment, stopping frequently on his daily tours of the construction site to congratulate a contractor or worker on the job. And Almond regularly deflects credit for a project that has had few major hitches, preferring instead to heap praise on his employees, his contractors, his bosses, the City Council, the Airport Advisory Board - just about anyone else who has had a role in the planning and construction of Austin-Bergstrom.

"These guys are operating on adrenaline alone," he said of the construction workers as he walked through the terminal recently “They feel like they're making history, and they've done everything to get it right."

Everywhere a sign

About a week before opening, Almond is driving around the loop that makes up the terminal access road. He's concerned about whether people will find it easy to navigate.

The signs that line the curbside are a big part of that ("You can never put in enough signing," he says), and Almond stops the truck on the baggage-claim level to squint at one of them, trying to determine why a sign saying "shuttle" points to an area where the shuttle won't be stopping.

Signs are a particular area of expertise for Almond. For 20 years, he has been part of industry groups that discuss airport signs – writing manuals and trying to standardize airport lettering so it's the same everywhere a person steps off the plane.

Little-known fact: Outdoor airport signs are printed in Helvetica medium. Experts spent years determining that the typeface is easiest to understand.

Almond's quest for perfect "signage" - that's what the industry calls it - illustrates his attention to the smaller details. Almond has more than a dozen managers reporting to him who can focus on their own projects, but his job requires that he be familiar with every aspect of the massive construction project.

Fresh from a job overseeing the design of a $125million expansion at San Jose International Airport as a consultant for California's HTB Inc., Almond joined Austin's Department of Aviation in February 1991 as the airport development manager. He began almost immediately working on a master plan for building the new airport and became project director after voters approved bonds to build the airport.

The work has not stopped since. It's just multiplied.

Ringing a few bells

In the last weeks of construction, Almond has worked through the weekends and often into the night. He attempts to keep his schedule cleared of meetings so he can make rounds of the construction sites - what he considers among the most important parts of his job.

"I just try to be the eyes and ears," Almond said. "I'm looking for signs of progress so I can decide whether or not I need to ring somebody's bell."

Ringing a bell, for Almond, is not as harsh as it sounds. It usually means he wants to ask someone what the problem is, then to try to fix it.

His employees say they've never seen him lose his temper. When dealing with contractors, Almond said he does everything possible to avoid confrontation. When the airport opening was delayed because Morganti Group Inc., the terminal contractor, was not finished with the construction, Almond steadfastly refused to point fingers in the media or to talk about penalties the contractor could be assessed. He was more focused on how to get the job done.

"The bottom line with me is: The work needs to get done and they're the only ones that can do that," he said.

Deputy Director Arnie Rosenberg, who works for airport consultant Parsons Brinckerhoff said Almond's ability to talk problems calmly in stride has set a steady tone for the project.

"A good manager says, 'We will cross that bridge, then cross the next one,' instead of getting panicked, Rosenberg said. "That's John. He's the consummate professional."

Jesus Garza agrees."He just doesn't panic " Austin's city manager said. “Everyone's watching this. There's been lot of difficult push and pull on it. But there's a great belief and trust in him to make the right decision”

While Almond's supporters can be found on the council, in the rank-and-file and on the citizen groups that advise the airport no high-profile job comes without critics.

Steve Grossman, project director for the terminal expansion in San Jose, where Almond worked before coming to Austin, said Almond's success at Austin Bergstrom is obvious to those in the industry.

"To be able to bring in a project like that in the way he has is a testament to his abilities," Grossman said. "I like to take a little bit of credit for encouraging him to take the Austin job to begin with."

Grossman, now director of aviation at Oakland International Airport, said he's considered trying to bring John Almond back to the Bay Area to help on an $800 million expansion there, "but I don't think he'd come back”.

Comments