This topic recorded the taxes and mandatory contributions that a medium-size company must have paid or withheld in a given year, as well as the administrative burden of paying taxes and contributions. The most recent round of data collection for the project was completed on May 1, 2019 covering for the Paying Taxes indicator calendar year 2018 (January 1, 2018 – December 31, 2018). See the methodology and video for more information.

To learn more about the results of Paying Taxes in calendar year 2018, see the Paying Taxes 2020 report.

Why it matters?

Why do tax rates and tax administration matter?

To foster economic growth and development governments need sustainable sources of funding for social programs and public investments. Programs providing health, education, infrastructure and other services are important to achieve the common goal of a prosperous, functional and orderly society. And they require that governments raise revenues. Taxation not only pays for public goods and services; it is also a key ingredient in the social contract between citizens and the economy. How taxes are raised and spent can determine a government’s very legitimacy. Holding governments accountable encourages the effective administration of tax revenues and, more widely, good public financial management.1

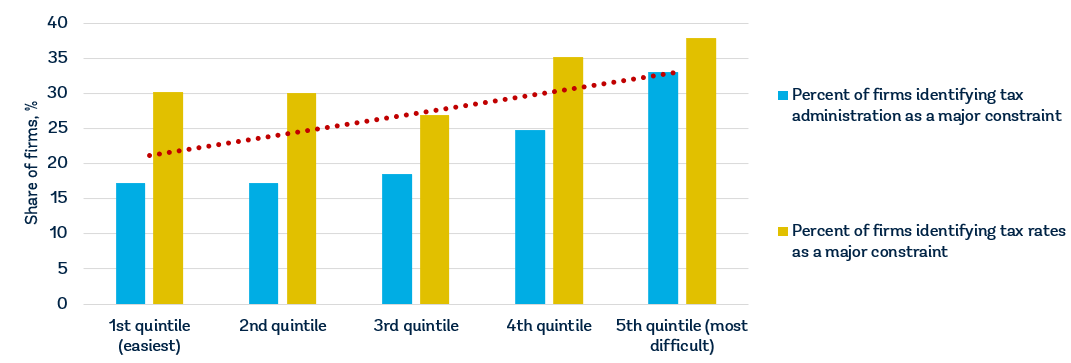

All governments need revenue, but the challenge is to carefully choose not only the level of tax rates but also the tax base. Governments also need to design a tax compliance system that will not discourage taxpayers from participating. Recent firm survey data for 147 economies show that companies consider tax rates to be among the top five constraints to their operations and tax administration to be among the top 11.2 Firms in economies that score better on the Doing Business ease of paying taxes indicators tend to perceive both tax rates and tax administration as less of an obstacle to business (figure 1).

Figure 1 - Tax administration and tax rates are perceived as less of an obstacle in economies that score better on the paying taxes indicators

Sources: Doing Business database; World Bank Enterprise Surveys (http://www.enterprisesurveys.org).

Note: the relationships are significant at the 1% level and remain significant when controlling for income per capita.

Why tax rates matter?

The amount of the tax cost for businesses matters for investment and growth. Where taxes are high, businesses are more inclined to opt out of the formal sector. A study shows that higher tax rates are associated with fewer formal businesses and lower private investment. A 10-percentage point increase in the effective corporate income tax rate is associated with a reduction in the ratio of investment to GDP of up to 2 percentage points and a decrease in the business entry rate of about 1 percentage point.3 A tax increase equivalent to 1% of GDP reduces output over the next three years by nearly 3%.4 Research looking at multinational firms’ decisions on where to invest suggests that a 1-percentage point increase in the statutory corporate income tax rate would reduce the local profits from existing investment by 1.3% on average.5 A 1-percentage point increase in the effective corporate income tax rate reduces the likelihood of establishing a subsidiary in an economy by 2.9%.6

Profit taxes are only part of the total business tax cost (around 39% on average). In República Bolivariana de Venezuela, for example, the nominal corporate income tax is based on a progressive scale of 15–34% of net income, but the total business tax bill—even after taking into account deductions and exemptions—is 73.31% of commercial profit owing to a series of other taxes (a profit tax, four labor taxes and contributions, a turnover tax, a property tax and a science, technology and innovation tax).

Keeping tax rates at a reasonable level can encourage the development of the private sector and the formalization of businesses. Modest tax rates are particularly important to small and medium-sizeenterprises, which contribute to economic growth and employment but do not add significantly to tax revenue.7 Typical distributions of tax revenue by firm size for economies in Sub-Saharan Africa and the Middle East and North Africa show that micro, small and medium-size enterprises make up more than 90% of taxpayers but contribute only 25–35% of tax revenue.8 Imposing high tax costs on businesses of this size might not add much to government tax revenue, but it might cause businesses to move to the informal sector or, even worse, cease operations.

In Brazil, the government created Simples Nacional, a tax regime designed to simplify the collection of taxes for micro and small enterprises. The program reduced overall tax costs by 8% and contributed to an increase of 11.6% in the business licensing rate, a 6.3% increase in the registration of microenterprises and a 7.2% increase in the number of firms registered with the tax authority. Revenue collections rose by 7.4% percent as a result of increased tax payments and social security contributions. Simples Nacional was also credited with increasing the revenue, profit, paid employment and fixed capital of formal-sector firms.9

Businesses care about what they get for their taxes. Quality infrastructure is critical for the sound functioning of an economy because it plays such a central role in determining the location of economic activity and the kinds of sectors that can develop. A healthy workforce is vital to an economy’s competitiveness and productivity—investing in the provision of health services is essential for both economic and moral reasons. Basic education increases the efficiency of each worker, and good-quality higher education and training allow economies to move up the value chain beyond simple production processes and products.

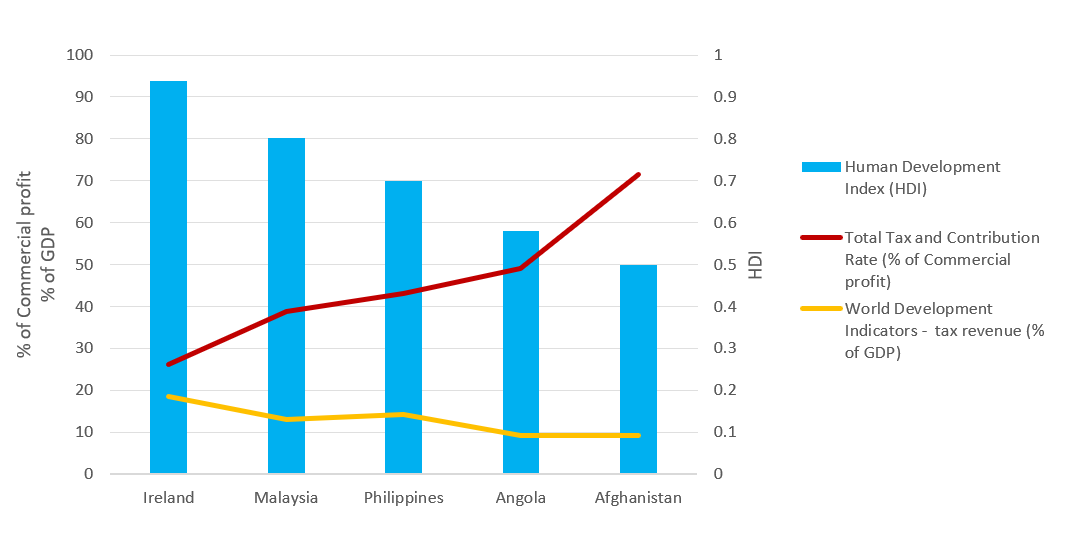

The efficiency with which tax revenue is converted into public goods and services varies around the world. Recent data from the World Development Indicators and the Human Development Index show that economies such as Ireland and Malaysia—which all have relatively low total tax rates—generate tax revenues efficiently and convert the gains into high-quality public goods and services (figure 2). The data show the opposite for Angola and Afghanistan. Economic development often increases the need for new tax revenue to finance rising public expenditure. At the same, time it requires an economy to be able to meet those needs. More important than the level of taxation, however, is how revenue is used. In developing economies high tax rates and weak tax administration are not the only reasons for low rates of tax collection. The size of the informal sector matters as well; the tax base is much narrower because most workers in the informal sector earn very low wages.

Figure 2 - High tax rates do not always lead to good public services

Sources: Doing Business database; Human Development Index 2018, World Bank database 2018.

Why tax administration matters

Efficient tax administration can help encourage businesses to become formally registered, thereby expanding the tax base and increasing tax revenues. Tax administration that is unfair and capricious is likely to bring the tax system into disrepute and reduce the government’s legitimacy. In many transition economies in the 1990s, the failure to improve tax administration when new tax systems were introduced resulted in the uneven imposition of taxes, widespread tax evasion and lower-than-expected tax revenue.10

Compliance with tax laws is important to keep the system working for all and supporting the programs and services that improve lives. One way to encourage compliance is to keep the rules as clear and simple as possible. Overly complicated tax systems are associated with high tax evasion. High tax compliance costs are associated with larger informal sectors, more corruption and less investment. Economies with simple, well-designed tax systems are able to boost businesses activity and, ultimately, investment and employment.11 New research shows that an important determinant of firm entry is the ease of paying taxes, regardless of the corporate tax rate. A study of 118 economies over six years found that a 10% reduction in the tax administrative burden—as measured by the number of tax payments per year and the time required to pay taxes—led to a 3% increase in annual business entry rates.12

Tax administration is changing as the ecosystem in which it operates becomes broader and deeper, mostly owing to the vast increase in digital information flows. Tax administrations are responding to these challenges through the introduction of new technology and analytical tools. They must rethink how they operate, offering the prospect of lower costs, increased compliance and incentives for compliant taxpayers.13 The government of Tajikistan has made tax reform a major priority for the country as it seeks to achieve its development goals. In 2013, Tajikistan launched the Tax Administration Reform Project and, as a result, the country built a more efficient, transparent and service-oriented tax system. The modernization of IT infrastructure and the introduction of a unified tax management system increased efficiency and reduced physical interactions between tax officials and taxpayers. Following the improvement of taxpayer services, the number of active firms and individual taxpayers filing taxes has doubled and revenue collections have risen strongly. A taxpayer in Tajikistan spent 28 days in 2016 complying with all tax-related regulations, compared with 37 days in 2012. 14

A low cost of tax compliance and efficient procedures can make a significant difference for firms. In Hong Kong SAR, China, for example, the standard case study firm would have to make only three payments a year, the lowest number of payments globally. In Qatar and Saudi Arabia, it would have to make four payments, still among the lowest in the world. In Estonia, complying with profit tax, value added tax (VAT) and labor taxes and contributions takes only 50 hours a year, around 6 working days.

Research finds that it takes a Doing Business case study company longer on average to comply with VAT than to comply with corporate income tax. However, the time it takes a company to comply with VAT requirements varies widely. Research shows that this is explained by variations in administrative practices and in how VAT is implemented. Compliance tends to take less time in economies where the same tax authority administers VAT and corporate income tax. The use of online filing and payment also greatly reduces compliance time. Frequency and length of VAT returns also matter; requirements to submit invoices or other documentation with the returns add to compliance time. Streamlining the compliance process and reducing the time needed to comply with the requirements is important for VAT systems to work efficiently.15

Why do postfiling processes matter?

Filing the tax return with the tax authority does not imply agreement on the final tax liability. Often, the ordeal of taxation starts after the tax return has been filed. Postfiling processes—such as claiming a VAT refund, undergoing a tax audit or appealing a tax assessment—can be the most challenging interaction that a business has with a tax authority. Businesses might have to invest more time and effort into the processes occurring after filing of tax returns than into the regular tax compliance procedures.

Why VAT refund systems matter?

The VAT refund is an integral component of any modern VAT system. In principle, VAT’s statutory incidence is on the final consumer, not on businesses. According to tax policy guidelines set out by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), a VAT system should be neutral and efficient. The absence of an efficient VAT refund system for businesses with an excess input VAT in a given tax period will undermine this goal. VAT could have a distortionary effect on market prices and competition and consequently constrain economic growth.16

Refund processes can be a major weakness of VAT systems. This view is supported by a study examining VAT administration refund mechanisms in 36 economies worldwide.17 Even in economies where refund procedures are in place, businesses often find the process complex. The study examined the tax authorities’ treatment of excess VAT credits, size of refund claims, procedures followed by refund claimants and time needed for the tax authorities to process refunds. The study found that statutory time limits for making refunds are crucial but often not applied in practice.

Delays and inefficiencies in the VAT refund systems are often the result of fears that the system might be abused and prone to fraud.18 Moved by this concern, many economies have established measures to moderate and limit the recourse to the VAT refund system and subject the refund claims to thorough procedural checks. That is also one of the reasons why, in some economies, it is not uncommon for a claim for a VAT refund to automatically trigger a costly audit, undermining the overall effectiveness of the system.

The Doing Business case study company, TaxpayerCo., is a domestic business that does not trade internationally. It performs a general industrial and commercial activity and it is in its second year of operation. TaxpayerCo. meets the VAT threshold for registration and its monthly sales and monthly operating expenses are fixed throughout the year, resulting in a positive output VAT payable within each accounting period. The case study scenario has been expanded to include a capital purchase of a machine in the month of June. This substantial capital expenditure results in input VAT exceeding output VAT in the month of June.

The results show that, in practice, only 107 of the economies covered by Doing Business allow for VAT cash refund in this scenario. This number excludes the 26 economies that do not levy VAT and five economies where the purchase of a machine is exempted from VAT.19 Some economies restrict the right to receive an immediate cash refund to specific types of taxpayers such as exporters, embassies and non-profit organizations. This is the case in 34 economies including Belarus, Bolivia, Colombia, the Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Kazakhstan, Mali and the Philippines.

In other economies businesses are only allowed to claim a cash refund after carrying forward the excess credit for a specified period of time (four example, four months). The net VAT balance is refunded to the business only after this period ends. This is the case in 26 economies of the 190 measured by Doing Business.

The legislation in other economies—typically those with a weaker administrative or financial capacity to handle cash refunds—may not permit refunds outright. Instead, tax authorities require businesses to carry forward a claim and offset an excess amount against future output VAT.

Insofar as procedural checks are concerned, in 77 of the 107 economies which allow for a VAT cash refund in the Doing Business case scenario, a claim for a VAT refund will probably lead to an additional review being conducted before approving the VAT cash refund. Effective audit programs and VAT refund payment systems are inextricably linked. Tax audits (direct and indirect) vary in their scope and complexity, ranging from a full audit—which typically entails a comprehensive examination of all information relevant to the calculation of a taxpayer’s tax liability in a given period—to a limited scope audit that is restricted to specific issues on the tax return or a single-issue audit that is limited to one item.

In Canada, Denmark, Italy and Norway a request for a VAT refund is likely to trigger a correspondence audit, which requires less interaction with the auditor and less paperwork. By contrast, in most economies in Sub-Saharan Africa, where an audit is likely to take place, taxpayers are exposed to a field audit in which the auditor visits the premises of a taxpayer.

As far as the format of the VAT refund request is concerned, in 52 of the 107 economies the VAT refund due is calculated and requested within the standard VAT return submitted in each accounting period. In the other economies, the request procedure varies from filing a separate application, letter or form for a VAT refund to completing a specific section in the VAT return as well as preparing some additional documentation to substantiate the claim. In these economies, businesses spend on average 5.5 hours gathering the required information, calculating the claim and preparing the refund application and other documentation before submitting them to the relevant authority.

Overall, the OECD high-income economies are the most efficient at processing VAT refunds with an average of 14.3 weeks to process reimbursement (including some economies where an audit is likely to be conducted). Economies in Europe and Central Asia also perform well with an average refund processing time of 23.1 weeks. These economies provide refunds in a manner that does not expose businesses to unnecessary administrative costs and detrimental cash flow impacts.

Doing Business data also show a positive correlation between the time to comply with a VAT refund process and the time to comply with filing the standard VAT return and payment of VAT liabilities. This relationship indicates that tax systems that are harder to comply with when filing taxes are more likely to be challenging throughout the process.

Why tax audits matter?

Tax audits play an important role in ensuring tax compliance. Nonetheless, a tax audit is one of the most sensitive interactions between a taxpayer and a tax authority. It imposes a burden on a taxpayer to a greater or lesser extent depending on the number and type of interactions (field visit by the auditor or office visit by the taxpayer) and the level of documentation requested by the auditor. It is therefore essential that the right legal framework is in place to ensure integrity in the way tax authorities carry out audits.20

A risk-based approach takes into consideration different aspects of a business such as historical compliance, industry and firm-specific characteristics, debt-credit ratios for VAT-registered businesses and the size of a business in order to better assess which businesses are most prone to tax evasion. One study showed that data-mining techniques for auditing, regardless of the technique, captured more noncompliant taxpayers than random audits.21

In a risk-based approach the exact criteria used to capture noncompliant firms, however, should be concealed to prevent taxpayers from purposefully planning how to avoid detection and to allow for a degree of uncertainty to drive voluntary compliance. 22 23 Most economies have risk assessment systems in place to select companies for tax audits and the basis on which these companies are selected is not disclosed. Despite being a postfiling procedure, audit strategies can have a fundamental impact on the way businesses file and pay taxes. To analyze audits of direct taxes the Doing Business case study scenario was expanded to assume that TaxpayerCo. made a simple error in the calculation of its income tax liability, leading to an incorrect corporate income tax return and consequently an underpayment of the income tax due. TaxpayerCo. detected the error and voluntarily notified the tax authority. In all economies that levy corporate income tax—only 10 out of 190 do not—taxpayers can notify the authorities of the error, submit an amended return and any additional documentation (typically a letter explaining the error and, in some cases, amended financial statements) and pay the difference immediately. Businesses spend 5.7 hours on average preparing the amended return and any additional documents, submitting the files and making payment. In 76 economies the error in the income tax return is likely to be subject to additional review (even following immediate notification by the taxpayer).

In 37 economies this error will lead to a comprehensive review of the income tax return, requiring that additional time be spent by businesses. In the majority of cases the auditor will visit the taxpayer’s premises. On average, it takes about 83 days for the tax authorities to start the comprehensive audit. In these cases, taxpayers will spend 24 hours complying with the requirements of the auditor, going through several rounds of interactions with the auditor during 10.3 weeks and wait 8.1 weeks for the auditor to issue the final decision on the tax assessment. Economies in the OECD high-income group and Central Asian economies have the easiest and simplest processes in place to correct a minor mistake in the income tax return. In 28 economies in the OECD high-income group a mistake in the income tax return does not trigger additional reviews by the tax authorities. Taxpayers are only required to submit an amended return and, in some cases, additional documentation and pay the difference in taxes due. Economies in Latin America and the Caribbean suffer the most from a lengthy process to correct a minor mistake in an income tax return, as in most cases it would involve an audit imposing a waiting time on taxpayers until the final assessment is issued.

---------------

NOTES

1 FIAS. 2009. “Taxation as State Building: Reforming Tax Systems for Political Stability and Sustainable Economic Growth.” World Bank Group, Washington, DC.

2 World Bank Enterprise Surveys (http://www.enterprisesurveys.org).

3 Djankov, Simeon, Tim Ganser, Caralee McLiesh, Rita Ramalho and Andrei Shleifer. 2010. “The Effect of Corporate Taxes on Investment and Entrepreneurship.” American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 2 (3): 31–64.

4 Romer, Christina, and David Romer. 2010. “The Macroeconomic Effects of Tax Changes: Estimates Based on a New Measure of Fiscal Shocks.” American Economic Review 100: 763–801.

5 Huizinga, Harry, and Luc Laeven. 2008. “International Profit Shifting within Multinationals: A Multi-Country Perspective.” Journal of Public Economics 92: 1164–82.

6 Nicodème, Gaëtan. 2008. “Corporate Income Tax and Economic Distortions.” CESifo Working Paper 2477, CESifo Group, Munich.

7 Hibbs, Douglas A., and Violeta Piculescu. 2010. “Tax Toleration and Tax Compliance: How Government Affects the Propensity of Firms to Enter the Unofficial Economy.” American Journal of Political Science 54 (1): 18–33.

8 International Tax Dialogue. 2007. “Taxation of Small and Medium Enterprises.” Background paper for the International Tax Dialogue Conference, Buenos Aires, October.

9 Fajnzylber, Pablo, William F. Maloney and Gabriel V. Montes-Rojas. 2011. “Does Formality Improve Micro-Firm Performance? Evidence from the Brazilian SIMPLES Program.” Journal of Development Economics94 (2): 262–76.

10 Bird, Richard. 2010. “Smart Tax Administration.” Economic Premise (World Bank) 36: 1–5.

11 Djankov, Simeon, Tim Ganser, Caralee McLiesh, Rita Ramalho and Andrei Shleifer. 2010. “The Effect of Corporate Taxes on Investment and Entrepreneurship.” American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 2 (3): 31–64.

12 Pontus Braunerhjelm, and Johan E. Eklund. 2014. “Taxes, Tax Administrative Burdens and New Firm Formation.” KYKLOS 67 (February): 1–11.

13 OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development). 2017. Comparative Information on OECD and Other Advanced and Emerging Economies. Paris, France: OECD.

14 IFC (International Finance Corporation). 2018. “Improved Tax Administration Can Increase Private Investment and Boost Economic Development in Tajikistan.” International Finance Corporation, Washington, DC.

15 Symons, Susan, Neville Howlett and Katia Ramirez Alcantara. 2010. The Impact of VAT Compliance on Business. London: PwC.

16 OECD (2014), Consumption Tax Trends 2014: VAT/GST and excise rates, trends and policy issues, OECD Publishing, Paris.

17 Graham Harrison and Russell Krelove 2005, “VAT Refunds: A Review of Country Experience” IMF Working Paper WB/05/218, Washington D.C.

18 Keen M., Smith S., 2007, “VAT Fraud and Evasion: What Do We Know, and What Can be Done?”. IMF Working Paper WP/07/31.

19 It is worth noting that 28 economies analyzed in Doing Business do not levy VAT.

20 OECD (2006), Tax Administration in OECD and Selected Non-OECD Countries: Comparative Information Series (2006), OECD Publishing, Paris.

21 Gupta, M., and V. Nagadevara. 2007. “Audit Selection Strategy for Improving Tax Compliance: Application of Data Mining Techniques.” In Foundations of E-government, eds. A. Agarwal and V. Ramana. Proceedings of the eleventh International Conference on e-Governance, Hyderabad, India, December 28–30.

22 Alm J., and McKee M., 2006, “Tax compliance as a coordination game”, Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, Vol. 54 (2004) 297–312

23 Khwaja, M. S., R. Awasthi, J. Loeprick, 2011, ”Risk-Based Tax Audits Approaches and Country Experiences”, World Bank, Washington, DC.

Comments